Result-oriented, fact-based, continuous

Encounter, Knowledge, Communication

We promote global responsibility and multilateral cooperation by networking key actors and leaders from Africa and Europe at our high-level events. Results and policy recommendations are prepared through studies and strategy papers while we are in continuous exchange with our network. Thus, we ensure that the dialogue has a lasting impact on political discourse. Our focus areas are business and global health as well as pressing political topics. In doing so, we also include the intersecting topics climate, advancement of women and digital matters in our program.

Featured Program Highlight

The Africa Roundtable

The Africa Roundtable is the forum for decision-makers from the political, business and civil society spheres in Europe-Africa cooperation. It deals with pressing issues and challenges of the neighboring continents and develops partnership-based solutions and models for future cooperation. Twice a year, the Africa Roundtable gathers its participants, alternating between the European and the African Continent. Prior publications ensure a fact-based discussion, which is concluded with action recommendations. The eponymous podcast and regular text contributions in pre- and post-processing, complete the program and ensure a continuous dialogue.

Program

Business for Future

Program

Resilient Health Systems

Program

The Africa Roundtable

Program

Future of International Cooperation

Podcast

The Africa Roundtable

Our Formats

Conference

The high-level format provides a stage for experiences and expertise, whose international appeal has a significant impact on the political dialogue. In close cooperation with our partner organizations, we gather different spheres around one shared topic.

Salon

Continuous dialogue creates awareness for the urgent questions of our time. In salons, renowned experts open the discussion with our curated guests from business, politics and society.

Circle

We believe in proximity building trust. Our most personal format therefore offers the opportunity to deepen the knowledge of our high-ranking guests in a small circle, together with an exchange of experiences, in dialogue.

Politics Briefing

Politics Briefing foster professional dialogue with policymakers. This format is aimed particularly at members of the Bundestag, but also at political actors in government, ministries or political foundations.

Bilateral Meeting

With strong networks, the global challenges of the European and African continents can be tackled together. That is why we network opinion leaders from both continents, bringing together those who belong together.

Digital Salon

Our digital dialog series “Global Perspectives on ...” highlights topics and developments relevant to Europe and Africa and invites decision-makers from both continents to discuss with our CEOs Rhoda Berger and Gregor Darmer.

Program

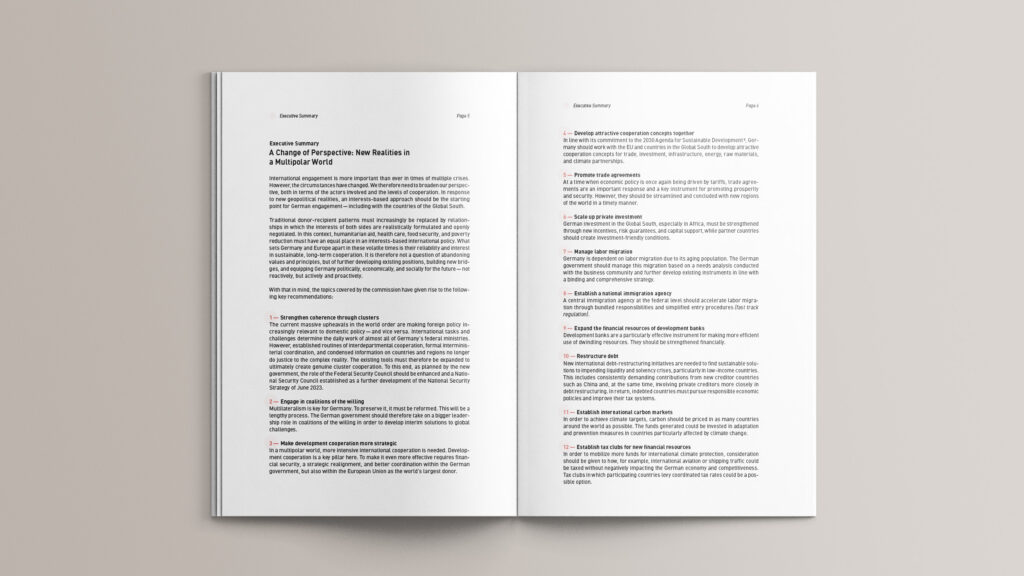

In the ninth edition of the Africa Roundtable, we discussed how Europe and Africa build partnerships that turn Africa's raw material wealth into local value creation.

This paper explores how Africa can add value to its critical minerals, boost local processing, and drive green industrialization while strengthening regional and global supply chains.

We discussed with State Secretary Niels Annen how development policy can be integrated into networked foreign, security, and economic policies.

US tariffs changes are causing new uncertainties in global trade. Together with ONE and Pinelopi K. Goldberg, we discussed how international development policy needs to be realigned.

As traditional trade relations shift, strengthening local value chains, enhancing trade agreements, and mobilizing private capital are key to building more resilient and mutually beneficial economies.

Our speaker James Irungu Mwangi shared his perspective on how to accelerate climate action and investment across Africa. Together, we discussed what it will take to mobilize the green finance needed.

Germany is a country of immigration. Building on our Commission's recommendations for action, we discussed ways to better manage and communicate labor migration.

Europe and Africa have the chance to advance technology and shape the future of the global space economy together through cooperation.

Amid shifting global dynamics, investing in Africa’s strengths in renewable energy and climate action is more urgent than ever. The action recommendations of the eighth conference.